Lou Gehrig was not a man to moan about his lot in life.

In fact he was just the opposite, which considering the set of cards life dealt him, was remarkable.

Gehrig was a legendary first baseman for the New York Yankees back in the 1920s and 30s.

A truly great player, he broke records like a chef breaking eggs for a meringue, but his greatest asset was his durability.

He played 2,130 consecutive games, which earned him the nickname of The Iron Horse.

Back then (before the modern era of 162 regular season games) it meant he never missed a game in FOURTEEN YEARS.

There were times he came close to sitting out. Twice – in the days before batting helmets – he was beaned and laid spark out, but played the next day. He played through various injuries, including broken hands, fingers, and other undetected fractures.

To say he was prepared to play through the pain barrier is akin to saying that Jedward don’t mind a bit of understated publicity.

Halfway through the 1938 season, the Iron Horse showed a few little signs that his legendary powers were waning.

When the Yankees gathered in Florida for Spring training in 1939 it was clear those abilities had been sapped.

Once the season started, his batting stats plummeted as he proved to be incapable of hitting a cow’s backside with a banjo. In the field he began to fumble routine balls, that went through his hands as though he had chocolate wrists and for somebody usually as fit as a robber’s dog, when he ran it looked as though he was dragging a dead horse through wet sand.

Clearly, something was wrong.

After playing his 2,130th consecutive game he told Yankees’ manager Joe McCarthy he was removing himself from the line-up for the next day’s game at Detroit Tigers “for the good of the team.”

Poignantly, Gehrig himself took the line-up card to the umpires before the game. The stadium announcer said; “Ladies and gentlemen, this is the first time Lou Gehrig’s name will not appear on the Yankee line-up in fourteen years.”

He was given a standing ovation by the Detroit crowd as he went to sit on the bench with tears in his eyes and a premonition in his heart.

He never played another Major League game.

Gehrig was clearly suffering from the type of debilitating illness that is the worse that any athlete can suffer; one which initially chips away at his skills and ability like a malevolent orc mining deep underground, before more rapidly eroding them.

The diagnosis was certainly a hammer blow when it came. On his 36th birthday Gehrig was told he was suffering from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), better known as Motor Neurone Disease, a condition affecting the central nervous system for which there was (and is) no cure. His prospects were, to say the least, grim. He faced increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of less than three years.

The cruel nature of the disease means it is painless and does not impart any mental impairment. In other words, the sufferer remains fully aware and alert to witness the decay of his bodily shell from the inside until the end.

Unsurprisingly, Gehrig announced his retirement and the news of his condition was released. July 4, 1939 was earmarked as Lou Gehrig day, a day full of pathos, where newsreel footage provides clues as to his condition. He was given various scrolls and trophies, every one of which he had to put down as he did not have the strength to hold them.

But what that day – and Lou Gehrig – lives on for, is the speech he gave.

You can look up the full version, just Google ‘Lou Gehrig farewell speech’. It’s passed into the pantheon of history of great speeches for which Americans get all gooey-eyed and mushy; Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, JFK’s “Ich bin ein Berliner,” Martin Luther King’s; “I have a dream” and Danny Kaye’s “The vessel with the pestle.”

Gehrig’s speech is different. It’s made by a man who knows the clock is ticking down on him, but at no time is it mawkish, sentimental, serf-serving or self-pitying.

It begins; “For the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.”

He then goes on to pay tribute to the men he played with and against, and winds up thus; “So I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

Two years later – a year less than his predicted lifespan – Lou Gehrig died, and in a strange, perverse memorial, the disease that killed him is now named after him.

Baseball is derided as rounders by those unfamiliar with its demands, not least of which is a staggering total of 162 games in the regular season. That’s pretty much playing every day between April and September, apart from travel days which can take teams from sea to shining sea, Miami to Seattle, San Diego to Boston.

It’s not uncommon for position players to play every game during a season and while the derisive comments from this side of the Atlantic may say all they are required to do is swing a stick and then stand on a bag, it doesn’t tell the full story.

Perhaps it’s the nature of the game that causes baseball – like cricket – to produce players and men of character.

Sure, baseball produces its share of rogues, scallywags and downright criminals, the same as any other sport.

Maybe it’s the American art of mythmaking that reaches its apogee in Hollywood that dictates their sporting legends are more manly, pure of thought and deed, and noble of spirit than those of other nations.

The American ability to create heroes, even extends to villains.

The 1912 Chicago White Sox have gone down in infamy as the most crooked team of all time. In the year the Titanic sank, the Black Sox plunged even deeper depths by tanking the World Series for money.

Among them was ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson, so named because he came from a dirt poor background.

Reckoned to be the finest player who lived, Jackson was found guilty and banned for life. Even though there was no convincing evidence that he trousered bribe money, Jackson was – rightly in many people’s eyes – guilty by association as he failed to blow the whistle on what was a pretty corrupt bunch of crooks.

From it, though, you have the apocryphal story of the raggedy-arsed urchin waiting outside the courtroom, half in disbelief and half in denial to ask his sporting hero the question as he came out; “Say it ain’t so, Joe.”

Never mind that this story has been proved to be untrue, you can see Shoeless Joe appear as a spook in Field Of Dreams.

However, take another story involving Joe Di Maggio, the former Mr Marilyn Monroe and the subject of a question of his location in Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Mrs Robinson’ (“Where have you gone, Joe Di Maggio?”).

Di Maggio is another of baseball’s all-time greats, who played eyeballs-out all the time, despite having the skills and ability which would have enabled him to coast through games.

On one particularly hot afternoon, The Yankee Clipper (as he was known) hustled down the baseline and slid head-first into base, beating the ball by a gnat’s whisker in a cloud of dust and getting the umpire’s “Safe!” call.

As he gingerly clambered to his feet, his pinstripe uniform covered in red clay and dusting himself off, the opposition first baseman indulged in a bit of chat.

By this time, Di Maggio was in the autumn of his career and had earned his place in baseball’s constellation of stars. Shaking his head and smiling in disbelief, the opponent said to Di Maggio; “Joe, I don’t know why you play like this every day. At this stage of your career, you could slow down. Why don’t you ease off?

“I can’t do that,” replied Di Maggio.

“Why not?” asked the opponent.

“Because,” replied Di Maggio, “there might be somebody in that crowd who has paid good money, and might not have seen me play before.”

Just digest that, will you? Here is a man who took such pride and passion in his profession that he couldn’t bear to think that he might short-change a fan, so he could not run the risk of appearing to not pull his weight.

Remember that the next time you watch a Premier League footballer tread lightly through the motions. An Adel Taraabt, Samir Nasri or other pea-hearted primadonna whose heart isn’t in it because he really wants to go and earn £100,000 a week at a dumb-ass club prepared to shell that type of money over to him.

And the next time Lewis Hamilton whines, whinges and points an accusing finger at his pit crew, or the car set-up, or any other weak-kneed excuse he can drum up for not winning a grand prix, perhaps he should think of a man who made no excuses and sought none.

Lou Gehrig never moaned or complained about his lot.

By John May

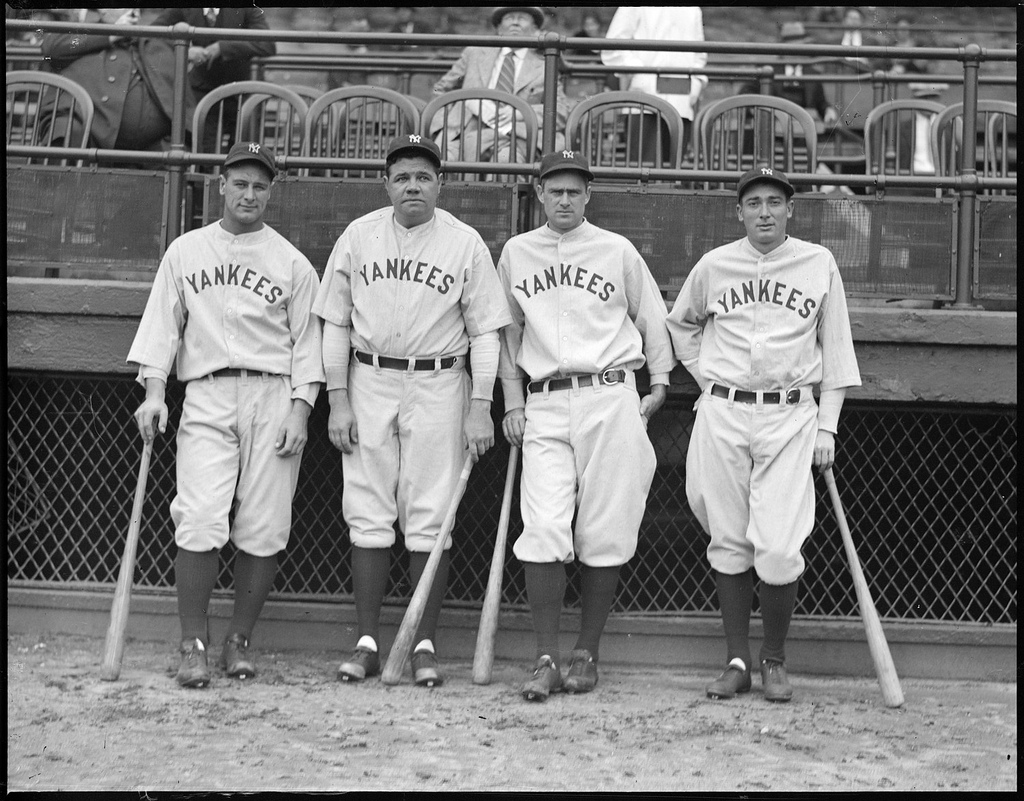

This photograph was provided by Boston Public Library.

Related

Must See

-

Basketball

/ 2 weeks agoFRIDAY FEATURE: Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and Nikola Jokic lead the 2025 NBA MVP race, but who deserves to win?

The 2025 NBA MVP race is shaping up to be one of the most...

-

Football

/ 2 weeks agoMohamed Salah SIGNS new two-year Liverpool contract

Mohamed Salah has signed a new contract at Liverpool until the summer of 2027...

-

Football

/ 5 months agoEric Cantona’s Manchester United story

Eric Cantona’s story at Manchester United is one of transformation, brilliance, and legend. Cantona...

By Scott Balaam